This excerpt begins in the Summer of 1999 after I have moved into my history professor’s grand house. For the first time she tells me stories from her past.

Dr. Ellsworth, late 90s

Chapter 5: History I

One evening we sit together around the kitchen table; windows raised to allow warm summer breezes inside. A decisive Scrabble victory in Babette’s favor lays out before us. Her lips curve upwards in jubilation.

“You are a little bit curious to learn more of my history, are you not, Wrahs?” she asks, eyes full of intrigue.

I nod, and with casual motions clear the board, not wishing my eagerness to show.

She leans back in her chair. “Be kind and fetch me some bubble water then. I will tell you a story.”

I rise and crack open a fresh bottle of mineral water from the supply shelf which contains around twenty. It fizzes into a glass which I bring over. She savors it and nods approvingly.

“I will never understand this American obsession with making every liquid they ingest as cold as the arctic. It can’t be healthy. You have perhaps noticed the upstairs freezer does not contain a single ice tray? I threw them away immediately after bringing it home.”

My professor shudders as if a painful memory haunts her.

“At any rate,” she begins, “in 1928 a teenage girl wandered into a hospital in Yakima, Washington. She was very pregnant and gave birth to a child, quite premature you understand. The father’s identity she either didn’t know or wouldn’t say. Afterward, she seemed to show almost no interest in the infant. And of course, this child was myself.” Babette beams.

“Well, it so happened a woman named Germaine worked at this hospital as a nurse. She came from a wealthy family called the Bonnefonts in southern France and married an American man named Robert Brown. They had no children, but wanted a family. She fell in love with this tiny baby who nobody cared about. Once I grew well enough to travel, Germaine snatched me from the bassinet, and they caught the first train out of town. We traveled by ship back to France, but there must have been some disagreement as Robert Brown disappeared from the picture soon afterward. Germaine raised me as her own and made every effort to remain undetected. Of course, the police knew who to look for and there was an international warrant for her arrest.

-The infant Dr. Ellsworth en route to France

-The infant Dr. Ellsworth en route to France

“So as a child I always remember unexpected moves. We traveled most often by train and the sound of rails at night put me to sleep. Such a reassuring sound. My mother would be quite high strung and nervous, but as soon as we left the station I could feel her relax. I have loved trains ever since. While a young child I discovered model railroads and kept a collection until recently but now my hands are too shaky for things with small parts.”

Babette rises. “Come to the study, I have some photographs from those times.”

We go to the next room and my professor rummages around the bottom drawer of her small writing desk. She removes a battered file folder and pours out several black and white photographs.

“Here is Germaine in 1920.”

I take this brown edged portrait and fixate on the image. A oval faced woman with dark hair tied back and elegant arched eyebrows faces the camera, her expression pleasant, yet calculating.

“She was beautiful.”

My professor chuckles. “Even yet her charms can affect one. Now there was someone who knew methods of getting what she wanted from the world. Not one to cross, that is for sure. A woman who lived quite a mysterious life. My adopted mother grew up amidst complete luxury in southern France but somehow ended up with the British Army in 1919 as they crushed an Irish uprising. Here, this picture is from Mullingar, Ireland, which was a flashpoint of the rebellion.”

I take this with deep interest. The sepia print shows Germaine in military uniform, her bobbed hair peeking out from under a cap. She regards the camera seriously and holds a long cigarette holder cocked in one hand. A cursive caption along the bottom reads ‘In His Majesty’s Service.’

“How on earth did something like this happen?” I ask, incredulous.

Babette shakes her head. “My mother would never speak of such things. She treated her past as a locked a chest never to be opened. I was truly amazed to find any photographs among her possessions after she died. If these were preserved as clues or merely out of nostalgia, I will never know. At any rate, here is one several years later in America of her with Robert Brown and myself.”

-Top right: Germaine and Robert Brown

-Top right: Germaine and Robert Brown

In this picture Germaine smiles with sheer joy. She stands next to a careworn man in a dark suit. He looms over her, almost two heads taller. The object of her delight is a tiny baby wrapped in white, it’s face down-turned.

“Brown looks quite a giant,” I observe.

Babette nods. “I never knew the man but he was said to be well over six feet tall. My adopted mother clearly loved him but never spoke of what happened between them. Ah, here is the last one I will show you for now.”

She passes me a closer photo, this time just of her mother with the child on her lap. I blink in amazement. Though still an infant, this is clearly my professor. The round head and facial features are unmistakable. It’s wispy scalp and plump cheeks have scarcely changed over seven decades later. Germaine gazes into this petulant face with adoration. I hand it back to Babette.

“So, the Bonnefonts, my adopted family, owned property all over, in Spain as well as France, so I soon spoke Spanish without having to learn in school. And they had political connections there, you know, of the very best sort, with General Franco.”

Babette pauses in admiration. “Now there was a talented leader. He kept Spain out of the Second World War, played each side for every advantage and then remained in power for another thirty years! Who would refuse to recognize the greatness of such a man?” She waits, daring me to contradict her.

“But George Orwell is your hero also!” I interject. In my professor’s library, Orwell’s books occupy a section of honor. “And he fought against Franco in the Spanish Civil War.”

“This is true,” Babette agrees, “yet even Orwell found qualities he could appreciate in the Nationalist cause. You may read about Catalonian anarchism and it seems quite admirable, but could they have defeated Franco on their own? Stalin’s communists were the only force organized enough to do so and had they succeeded, I wonder what state we would find Spain in today.”

I let the subject drop and she continues.

“You see, my family understood how to recognize authority and stay on its good side. That is a lesson some of us haven’t learned yet.” She smiles pointedly. The week before I had been thrown out of a downtown newspaper’s office with several other activists while distributing anti-capitalist leaflets.

“Of course, you are absolutely correct to be angry!” she continues, “but being right is no guarantee of survival, and that is what counts. Do you know who my true hero is? It is Joseph Fouche, of the French secret police. He served under Jacobin, Napoleonic and Bourbon regimes in the late eighteenth century. One might say, ‘Arrest Catholic authorities’ or next ‘Defend the monarchy’ but he did his duty, made sure not to become too compromised by any one side and do you know what, he survived them all and lived out his days in great comfort!” Babette’s eyes flash.

“So, my mother did all she could to prevent discovery. Of course, the authorities looked for a kidnapped girl. Well, clever woman that she was, it made sense to raise me so I could pass as either gender. She discovered for a little extra money I could be enrolled in Catholic school as a male. Now, oddly enough among the Southern French, my family wasn’t even Catholic, they disliked the church in fact and thought my mother mad, but it helped preserve her secret. Come along!”

Babette leads me to the living room and gestures at a large oil canvas on the mantelpiece. It depicts a grandiose white stone mansion with grandiose circular drive. The crescent staircase leads to its main entrance behind a large fountain surrounded by flowers. Seagulls fly overhead. In the foreground, a round faced child peers through large spectacles. He is dressed in a blue and white altar boys gown and further back, three adults cluster underneath a tall gas lamp post. One man in a white shirt stands next to a brunette woman and on her other side, an elderly gentleman wearing some kind of blue uniform strikes a dignified pose.

“Here is the Chateau du Lac, where we often lived. A beautiful old house, build around 1760 I believe. This is the Sigean region, quite close to the Mediterranean coast near Narbonne. As you can see, I enjoyed an entirely high class upbringing. But even for a member of the bourgeoisie, I experienced quite an extraordinary childhood in rather unusual surroundings. As I said, we kept close to some of the best families in Spain and traveled there often, but later developed connections with many wealthy Russians exiles as well.”

She sits down on a couch but I stand and examine the painting.

“This is you then?” I ask, gesturing at the youth.

Babette nods.

“I always participated so enthusiastically in the religious rituals. It’s complete rubbish, of course, but the genius of a Catholic education is that it never goes away. I would as soon chop off my right hand than abandon mass. Protestants foolishly never mastered guilt, though it’s such a powerful tool. You, with your deplorable Presbyterian upbringing couldn’t possibly understand.”

I shrug in acknowledgment. “The Russians…”

“Yes, them,” she continues. “Probably the most well known was Prince Felix Yusupov. You know of him, who assassinated the monk Rasputin in 1916? He poisoned, shot and finally drowned the man. I remember sitting on Yusupov’s lap, oh, he had terrible breath and smelled so strongly of cigars.”

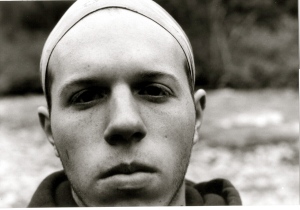

Prince Felix Yusupov as a young man